Are Undocumented People Seeking Sanctuary in US Churches Safe?

Aline Barros/VOA News

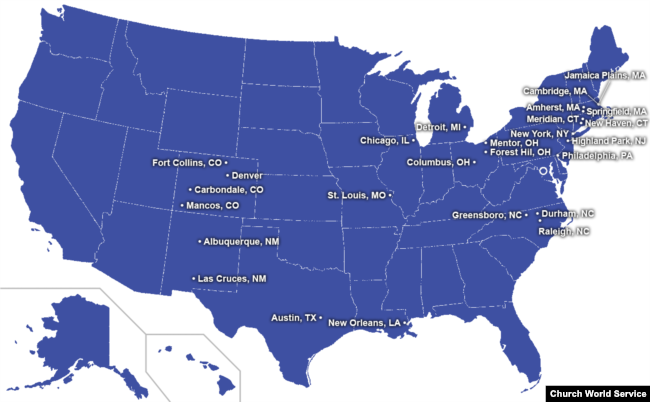

The number of undocumented people taking refuge in places of worship across the United States has increased six-fold in the past 15 months. Nationwide, there are now at least 42 people trying to avoid deportation by living in sanctuary in 28 U.S. cities.

“We didn’t see the numbers go up until after the [presidential] elections … when it was like seven people. Now you have over 40 people that are currently taking sanctuary,” Myrna Orozco, an associate with the Church World Service’s Immigration and Refugee Program, told VOA.

The number of churches, mosques and synagogues offering sanctuary nationwide has also grown. According to CWS, the number of interfaith congregations that have signed up to be part of the sanctuary movement has increased from 400 to more than 1,100.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement regards places of worship as sensitive locations, along with schools and hospitals, and avoids making arrests at those places.

“Enforcement actions may occur at sensitive locations in limited circumstances, but will generally be avoided,” ICE spokesman John Mohan wrote in response to a VOA query.

But ICE’s policy is just a policy and not protected by law. And it is subject to change. While immigrant advocates have long regarded courthouses as sensitive locations, ICE does not, having issued a policy directive just this past January for enforcement actions in courthouses.

As a result of their murky status, sensitive locations are a sensitive subject with immigration lawyers and advocates, many of whom declined to talk to VOA about the issue.

Knocking on sanctuary doors

Though she cannot leave the South Congregation Church on Maple Street in Springfield, Massachusetts, Gizella Collazo sees her two American born children regularly. They come and go as they please, as does Collazo’s U.S. citizen husband.

A Peruvian who has lived in the U.S. for 17 years, Collazo is the latest undocumented immigrant to seek sanctuary in a church; she has been at South Congregation since late March avoiding a deportation order.

She had hardly been there a week when Springfield officials conducted a health and safety inspection at the church. With a warrant issued by Western District Housing Court, city officials found no major housing code violations although the church did have to do some minor fixes including replacing a door lock.

Local news outlets reported that the inspection was at the instigation of Springfield Democratic Mayor Domenic Sarno who opposed the church’s decision to offer sanctuary.

Sarno told MassLive that he is in favor of legal immigrants but will not defend the ones who’ve broken the law.

“And I’m not going to become a sanctuary city,” he told MassLive, although sanctuary jurisdictions, which choose not to cooperate with federal immigration authorities, are different from places of worship that offer sanctuary.

CWS’ Orozco says congregations that offer sanctuary are careful to upgrade housing codes and regulations, a process that can take months before sanctuary is ever offered.

«Cities where people are living have the right to make sure that the living codes are up to date and it’s a little different from like an actual enforcement action from immigration [authorities,] because the city has to make sure that there are living conditions where people are at,» she says.

Orozco thinks the inspection was just «the mayor trying to take retaliation» against this particular church.

«If immigration were to show up at a congregation, most of the congregations that are having somebody would expect that they would do so with a warrant. And knowing that they would be essentially violating their own policy of not conducting enforcement operations at places and houses of worship.»

Sanctuary congregations, she says, ensure nobody comes in without an official warrant signed by a judge.

Victim or lawbreaker?

At the heart of the controversy, Gizella Collazo remains at the church.

She has no criminal record, but immigration officials say she entered the country with “fraudulent” documents. She has been trying to adjust her status since her marriage in 2006. But immigration advocates say she had complications changing her status due to “multiple legal errors” thus putting her on a path to an order of removal.

“She just wants to be with her family. This is the country of her kids and her husband. She wants to stay here with them. This is the country that she knows as her own and she’s been here 17 years. This is where she got married,” Emily Rodriguez, community organizer at Pioneer Valley Project told VOA.

Collazo must now fight the deportation order in court before adjusting her status.

“It has taken her 11 years to work on her documents, something that could’ve been done within three years, has taken her over 11 years to, to be able to fix her status because of a wrong assessment in her case,” Rodriguez said.

ICE says that Collazo entered the U.S. illegally on a fraudulent passport. She was granted voluntary departure by a judge in 2012. ICE said she had agreed to voluntarily leave the U.S. after multiple appeals were denied.

“However, after originally agreeing to voluntarily depart the country Ms. (Collazo), on March 26, 2018, took refuge at a church in Springfield, Massachusetts in an attempt to avoid complying with a federal judge’s order,” ICE’s Mohan wrote.