On Ellis Island, a Wall Honors Immigrants Old and New

VOA NEWS – Ramon Taylor

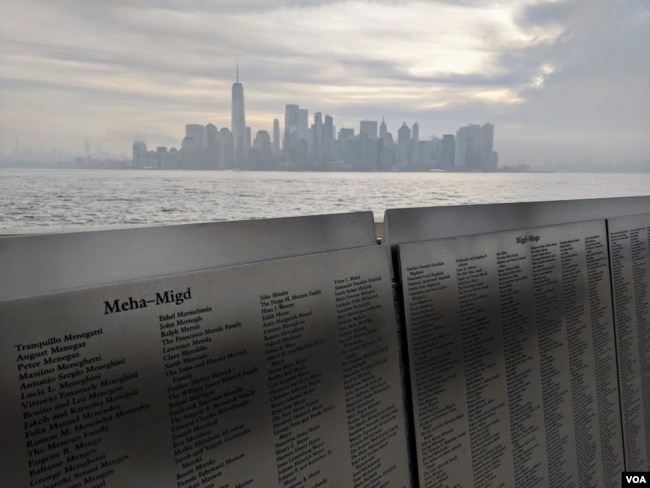

ELLIS ISLAND, NEW YORK — It may surprise no one to see names like «The Russo Family» from Sicily, Italy, or Anton Ivanovich Malygin from St. Petersburg, Russia, inscribed on Ellis Island’s American Immigrant Wall of Honor — a manifestation of common migration patterns to the United States from Europe more than a century ago.

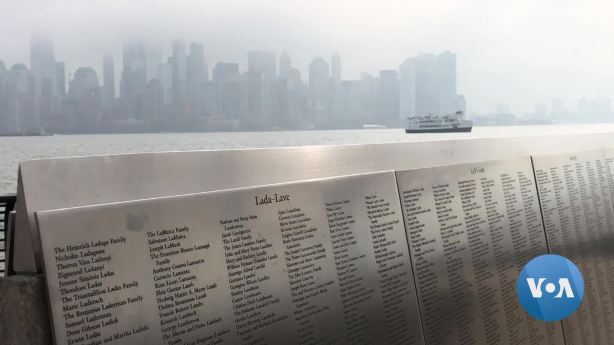

But on a nearby panel, reflecting the Upper New York Bay and the shapes of visitors in its stainless steel, are the names «Topiltzin and Angela Martínez Family» from Honduras; «Teresa and Rosa E. López» from Puerto Barrios, Guatemala; and «Jaime F. Hernández» from El Salvador — immigrants who did not disembark on Ellis Island, but are memorialized for posterity nonetheless.

«Everybody wants to be honored,» said Stephen Briganti, president and CEO of the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. «They want to be remembered. They want their moment of arrival in America to be something that is memorialized. And in a small way, that’s what we can do here.»

Outside the Great Hall at the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, 775,000 names are inscribed on 770 panels, formed in a semicircle wall facing New York’s Lower Manhattan skyline.

It’s not the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation that decides who is engraved, but immigrants and descendants of immigrants, old and new.

At its onset, a price tag of $100 earned you an individual slot.

«We could get million-dollar gifts from corporations, but this was an island of people. And generally, it was an island where poor people came. So, we wanted to make it possible for them or their descendants to honor them,» Briganti said.

Message to recent arrivals

What began in 1987 as a fundraising tool to restore and maintain Ellis Island, including the Wall of Honor, became a sensation across coastal cities and industrial hubs where the descendants of Ellis Island-era immigrants had largely settled.

As immigration patterns changed, so did the surnames on the wall itself. In the years since its creation, nearly every nationality is represented, including American Indian settlers and «those who endured forced migration from slavery,» according to the foundation’s website.

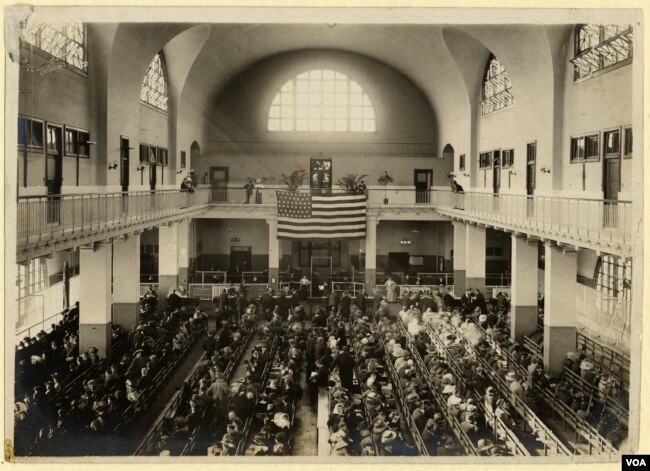

Chicago native Erin Josen’s late great-grandparents from Russia and Lithuania are among the 12 million immigrants who underwent vetting in the Registry Room at Ellis Island.

Visiting the wall where they are also honored, she said the difficulties that earlier immigrants faced should serve as a beacon of hope to recent arrivals.

«If I were a first- or second-generation [American], I would feel, like, ‘Wow, these people can go through all this adversity, and all this hardship — with the screenings, being judged, being told, «We don’t want you here,» but yet they are able to grow families and have third-, fourth-, fifth-generation families,’ » Josen said.

«I think that does give hope that they can have families that grow and do the same.»

‘Populating of America’

From 1892 until 1931 — the processing station’s peak years — 4.4 million passengers traveled to Ellis Island from Italy and Russia alone. In the modern immigration wave, 1965 to the present, more than three-quarters of new immigrants come from Latin America and South and East Asia.

Visiting from southern France, Ramundxo Noblea and Céline Uhart look to the Wall of Honor as a documented reminder of the constant struggles faced by new Americans, escaping dictatorship and other hardships.

«In France, it’s rare that immigrants are celebrated,» Noblea said. «From my perspective, it’s the same in the U.S. It’s a young country, so no one is a native of anywhere.»

«This is the story of the populating of America,» Briganti said. «You can’t underestimate the importance of people wanting to honor their arrival.»