On Balmy, Below-Zero Day at South Pole, There’s Work to Do

After a month at the South Pole, you begin to adapt to the frigid conditions.

Your body becomes more efficient at generating heat and your metabolism shifts into overdrive — every calorie you consume is burned.

As your tolerance of the polar environment changes, so do your perceptions of warm and cold. My first week on station was mind-numbingly chilly, temperatures hovered around minus 42 Celsius (minus -45 Fahrenheit).

This week has been delightfully balmy, with highs between minus 23 Celsius and minus 20 Celsius (minus 10 Fahrenheit and minus 4 Fahrenheit).

SOUTH POLE JOURNAL

Refael Klein blogs about his year working and living at the South Pole. Read his earlier posts here.

It feels bizarre saying that temperatures below zero are warm, but for us Polies, any climatic condition that allows you to walk on the ice without a balaclava is temperate.

When the weather is warm, we try to spend more of our time working on tasks outside. Even though it’s summer, temperatures can change quickly, and if you don’t take advantage of a pleasant day, Mother Nature seems to notice, and usually drums up a big storm in retribution.

This week, we have been working on setting up and installing a Brewer Spectrophotometer. The instrument was sent to us by Environment Canada, the Canadian equivalent of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and is used for measuring ultra violet radiation (UV) and total column ozone.

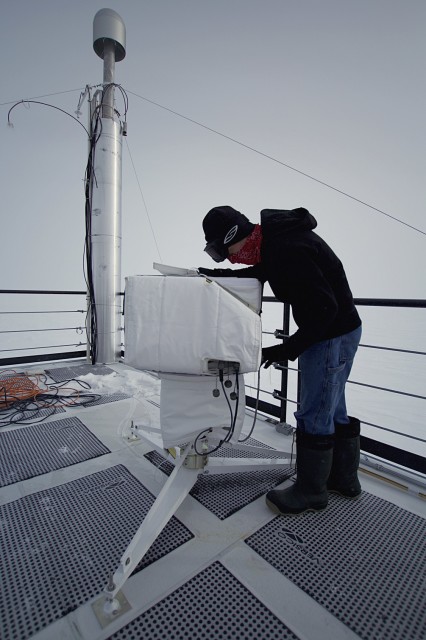

The author calibrating the Brewer Spectrophotometer to line up with the sun, a difficult feat on a cloudy day. (Photo by Hunter Davis)

Ozone is one of the many trace gasses that exist in the stratosphere. It is comprised of three oxygen molecules held together in double bonds and is formed when molecular oxygen and elemental oxygen react under the influence of light. Ozone absorbs UV radiation, minimizing the amount that reaches the planet’s surface, protecting biological organisms, like ourselves, from harmful wavelengths of solar energy.

The portion of the stratosphere that contains ozone in the highest concentration is known as the ozone layer. We monitor the thickness of the ozone layer using a variety of instrumentation.

At the Atmospheric Research Observatory (ARO), NOAA uses a ground-based, manually-operated apparatus called a Dobson Spectrophotometer and also launches weather balloons with ozone measuring devices attached to them.

Unlike NOAA’s equipment, the Brewer operates automatically and continuously measures the total amount of ozone in the atmosphere. It’s a good complement to NOAA’s suite of instruments, and allows scientists to compare results from three separate experiments.

This means greater accuracy in publications and better data for legislators to base environmental policy on.

The Brewer is comprised of three parts: a large metal tripod that everything sits on, a tracker box that controls the movement of the device, and the instrument head, which is bolted to the top of the tracker. When it is all put together, the instrument weighs about 45 kilos (100 pounds) and looks like a large white Igloo cooler.

After assembling and testing the Brewer inside, we broke it down and moved it to the roof. Skies were overcast, but it was warm, around minus 21 Celsius (minus 6 Fahrenheit). Working without bulky gloves, the installation took us little less than an hour.

The Dobson Spectrophotometer, the predecessor to the Brewer, was invented in the 1920s. The two at ARO are updated models, but work largely off the same principles as the originals. (Photo by Hunter Davis)

Back inside, we monitored the instrument’s performance on a computer. The Brewer was receiving and executing commands properly, but it wasn’t perfectly aligned with the sun, a must for accurate measurements.

With the day only getting cloudier, it looked like we had lost our opportunity to calibrate its position. Oh well. We were 99 percent there and it was late in the day. I was beginning to get hungry.

I grabbed my hat and water bottle from my office, walked out the bottom floor of the observatory and began the quarter mile walk back towards the main station. As I passed the geographic pole, I felt a rivulet of sweat fall from brow to my cheek. What a bizarre feeling — to perspire when it’s below zero.

I removed my jacket and mittens and, in the stillness of the early evening, enjoyed a warmth and heat that I had not felt for many weeks. What extravagance. A smile bridged across my face. I looked north, and saw a patch of clear sky begin to form on the horizon.

Perhaps tomorrow would be as beautiful.