Anxiety for US-born Kids of Families Facing Deportation

VOA News/Aline Barros & June Soh

BETHESDA, MARYLAND — Jacqueline Landaverde, 17, applied to colleges hoping to study political science and law.

Kevin Palma, also 17, wants to major in health sciences and eventually become a cardiovascular surgeon.

While both live in Massachusetts and were born in the U.S., their parents weren’t. They came to the U.S. under the Temporary Protected Status Program (TPS). TPS granted them legal status in the U.S. and allowed them to work. As the name indicates, TPS was always intended to be temporary while the countries affected recovered from natural disasters or political crises.

Even if a person lives and works legally in the United States as a TPS beneficiary for many years like Palma’s and Landaverde’s parents, it does not give recipients a path to permanent residence or a green card.

And in September 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security [DHS] announced it would end the program for six of 10 protected countries. Immigrants from El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Sudan — more than 400,000 individuals — would lose their legal status including both teenagers’ parents who are from El Salvador.

TPS was slated to end for almost 300,000 Salvadorans, Sept. 9, 2019.

Broken families

Both young people expect their lives to change dramatically if their parents are forced to return to El Salvador. Almost certainly it would end their dreams of going to college.

“When it struck me was about two years ago, in 2017, when I was actually told the consequences that would happen. Basically, family separation … I would have to stay here. I’d have to get a full-time job to take care of my siblings,” Palma said.

Landaverde’s situation is no different. As the eldest in her family, she, too, would have to get a job and take care of her three siblings. Finding herself potentially in this situation has been a shock.

“Growing up I never knew. I just knew protection and my parents were legal in this country. … We heard these rumors ‘TPS is going to be canceled.’ And then I confronted my parents,” Landaverde said.

Landaverde said her parents gave a “brief explanation” and said, “It has kept us here in this country.”

But she really understood what it meant when she did her own research and discovered the Massachusetts Temporary Protected Status Committee, which organizes rallies and meetings, and keeps TPS holders informed.

“That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, this is TPS, and if it’s taken away, this is going to happen,’” she said.

Stage play, real stories

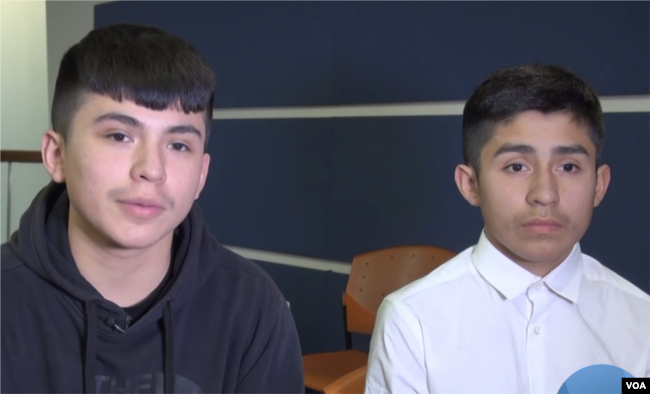

VOA met with both high school seniors and their friends in Bethesda, Maryland, at the Imagination Stage Theatre where, along with 11 other children, ages 10 to 17, they performed The Last Dream a project from the Boston Experimental Theatre in which children of TPS recipients tell their real life stories.

The project, organizers said, was born after staff from the Boston Experimental Theatre heard the stories from children of TPS recipients.

“We need to grow the hell up and fast. Do you not understand that this might be our last Christmas together?” asks one of the young actors during a birthday party in The Last Dream.

“Talking about what? What do you mean?” another child asks, bewildered.

“I don’t think anyone can watch this, walk away, and say ‘I am going to live the same way’ or ‘I’m going to continue to ignore them,’” Jared Wright, one of the playwrights, told VOA.

Audience member Beth Brooks-Mwano, who felt grateful for the children sharing their stories so “generously,” said that she took away a new understanding.

“I can help by actually bringing awareness,” she said.

The Last Dream was part of a three-day series of events in which thousands of TPS holders came to the nation’s capital to speak with legislators and lobby for a solution, giving TPS recipients a path to permanent residence in the U.S. While Democrats support this kind of solution, most Republicans are against it.

‘Will you help me?’

In October, a U.S. federal judge blocked the Trump administration from ending TPS protections for people from Haiti, Sudan, Nicaragua and El Salvador while the terminations were contested in court.

The U.S. Justice Department criticized the stay saying the court wrongly took the power to decide such matters from the executive branch of government. The government has filed an appeal of the injunction to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Currently, there are a total of seven court challenges to TPS terminations under the Trump administration.

In one case, Saget v. Trump, a decision is expected in March.

The Last Dream presentations are ongoing around the country. Palma and Landaverde should hear from colleges around April and May.

“My plan is to be in college in a year, but I don’t know if that is going to happen because in September is the termination of El Salvadoran TPS,” Palma said.

Sofia Landaverde, Jacqueline’s 10-year-old sister, whose birthday it is in the play, shared among tears, deep breaths and long pauses how sad she was when she found out about TPS.

“Nobody wants to be separated from their parents because every child deserves to be with their parents,” she said.

“I think they (Sofia’s parents) would choose for us to stay here because there is a lot of violence in El Salvador. There’s a lot of stuff going on that is not really good for kids,” she said.

On stage at the end of the play, Sofia is alone. She is afraid she won’t have her parents for her birthday next year.

In front of an audience of more than 50 people, she asks, “Will you help me? Will you?”